Face Lab

Caroline Wilkinson and Mark Roughley are two members of the Posthmous World project team.

They both work at Face Lab – a research centre that specialises in facial identity and reconstruction

for forensics and archaeology, based at Liverpool John Moores University. They have achieved a high public profile and many awards for their recreation of key historical figures such as Richard III and Robert the Bruce. This makes them experts in body modelling and visualisation – two central aspects of this project. In December I decided it was time to pay them a visit and see how they do it.

Face Lab is a leading example of the value of combining the arts and sciences in interdisciplinary research. Caroline has a medical art and anatomy background, Mark originally came from illustration. Sarah Shrimpton, another researcher, was a fine art graduate. Forensic and medical art is not an exact science. It is not about ‘realism’. It is about what will make a face recognisable or believable.

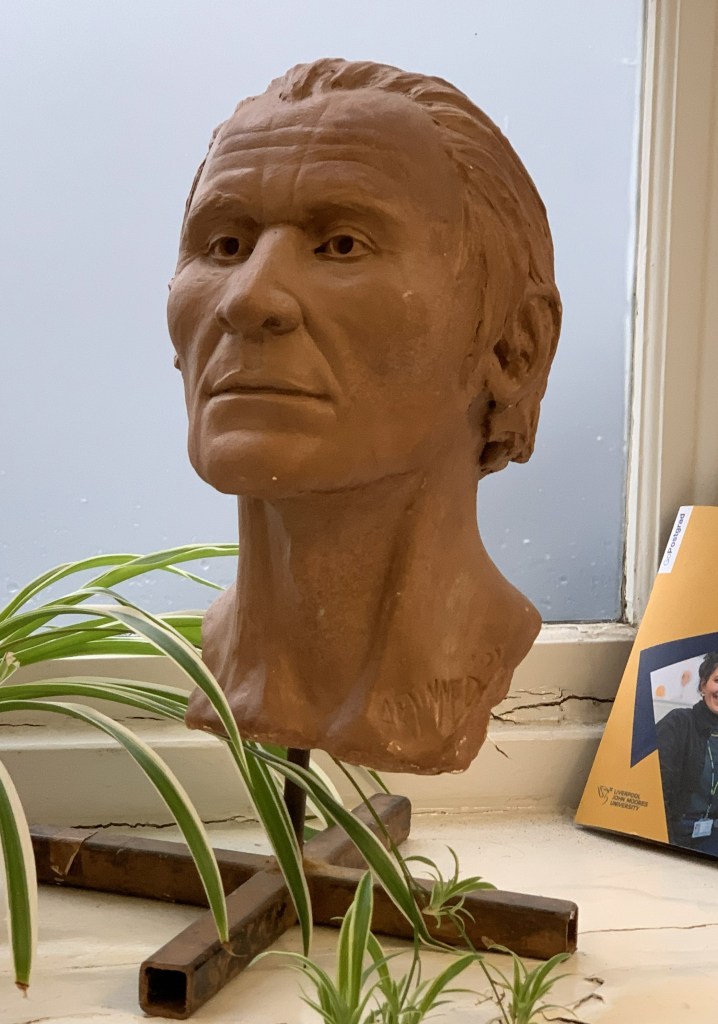

Face Lab’s work is now all digital but artists used to use physical media such as this clay bust. Despite this, a lot of the digital models are also 3D printed.

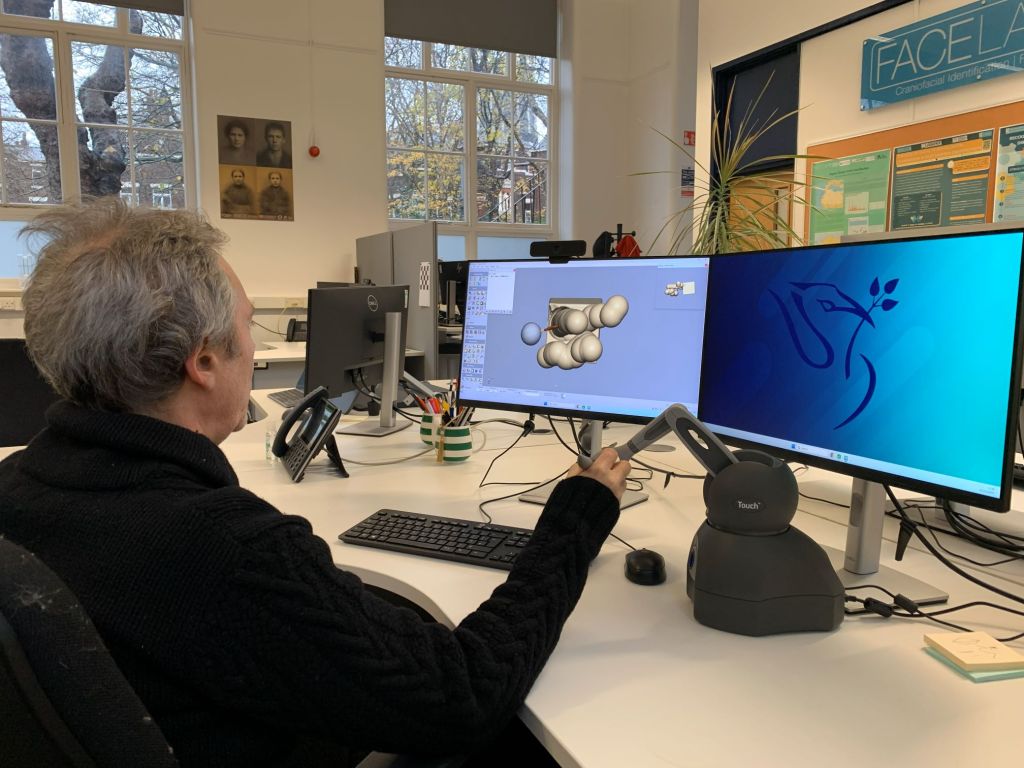

Face Lab employs a 3D modelling programme called Freeform Modelling Plus by Geomagic. This is attached to a Phantom haptic (force-feedback) interface which mimics a manual sculpting process. As you move the stylus it resists your movements as though you have come up against the physical surface of the head, like working in virtual clay. I tried it for a few minutes and found it very unusual. Caroline explained that it takes a while to get used to your hand feeling something that it not where your eye sees it. Then after some practice it suddenly clicks.

I asked why these haptic interfaces are more useful than the purely screen based. Caroline told me that some things are easier to feel than to see. It is easy to forget in the age of digital media that physical sculpting was always a practice of perceiving through touch. As an example she pointed out Whitnall’s tubercle. This is a bump on the outer rim of the eye socket of the skull to which ligaments are attached, such as the ones that hold your eyelids in place. This acts as key anatomical reference point when modelling the eye.

DOES FORENSIC ART NEED ARTISTS?

In her 2015 Review of Forensic Art, Caroline Wilkinson described how forensic artists had come under fire for being too subjective and how forensic art had at times became a controversial term. [2]

The scientific community attempted to create methods that reduced the reliance on artistic training and increase the application of scientific standards (such as with the well-known Identikit system). Each practitioner attempted to suggest that their methods were more scientific and less artistic than the next.

Yet it is still artists who best understand faces in a way that enables them to depict a person in a believable manner. It is not really a question of accuracy or at least not in a technical sense. Sometimes “caricatures are more recognisable than accurate faces” and high detail may not be more effective than low detail. When comparing purely scientific facial depiction systems with those that include the work of artists, the results speak for themselves – “while computers are objective, reliable, and reproducible… facial images created by artists produce a greater response from the public than computer-generated images”. However, forensic artists will still have to “justify the decisions and processes followed” if the results are ever questioned. A forensic artist has responsibilities that weigh more heavily, requiring a more methodological approach and constant self-reflection as they work.

You can learn more about Face Lab’s work here:

Face Lab’s describe their work as “the depiction and identification of unknown bodies for forensic investigation or historical figures for archaeological interpretation.” Face Lab do a lot of regular forensic work for the police to help identify human remains. This video (2018) shows the main stages of a typical facial reconstruction from skeleton.

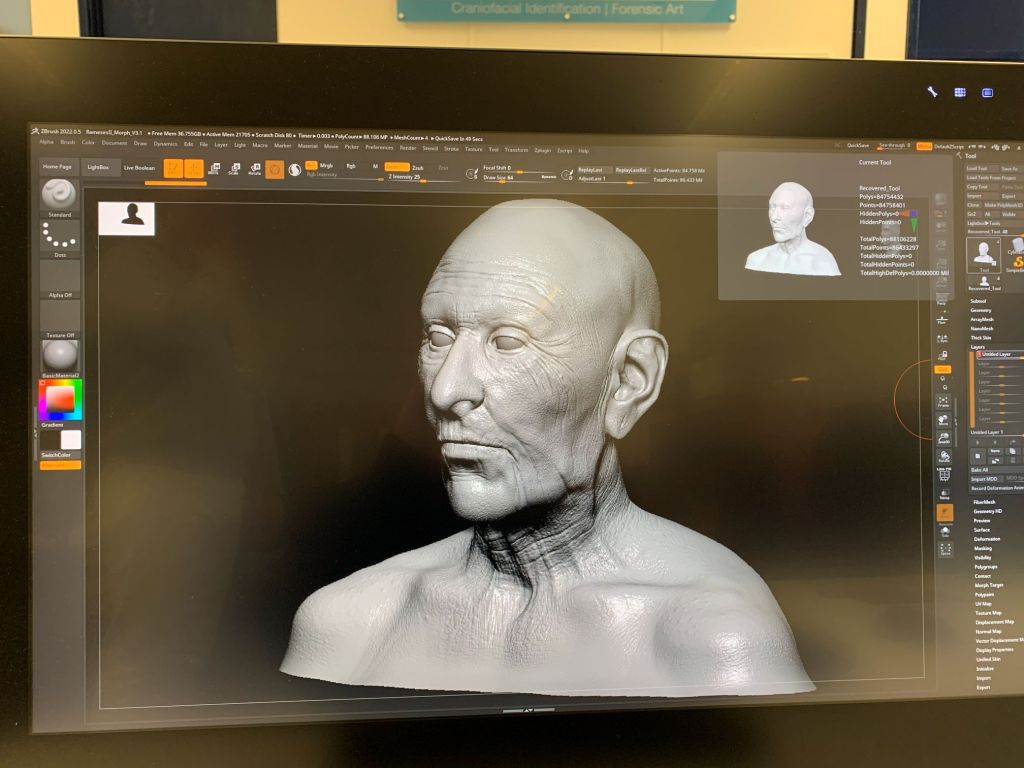

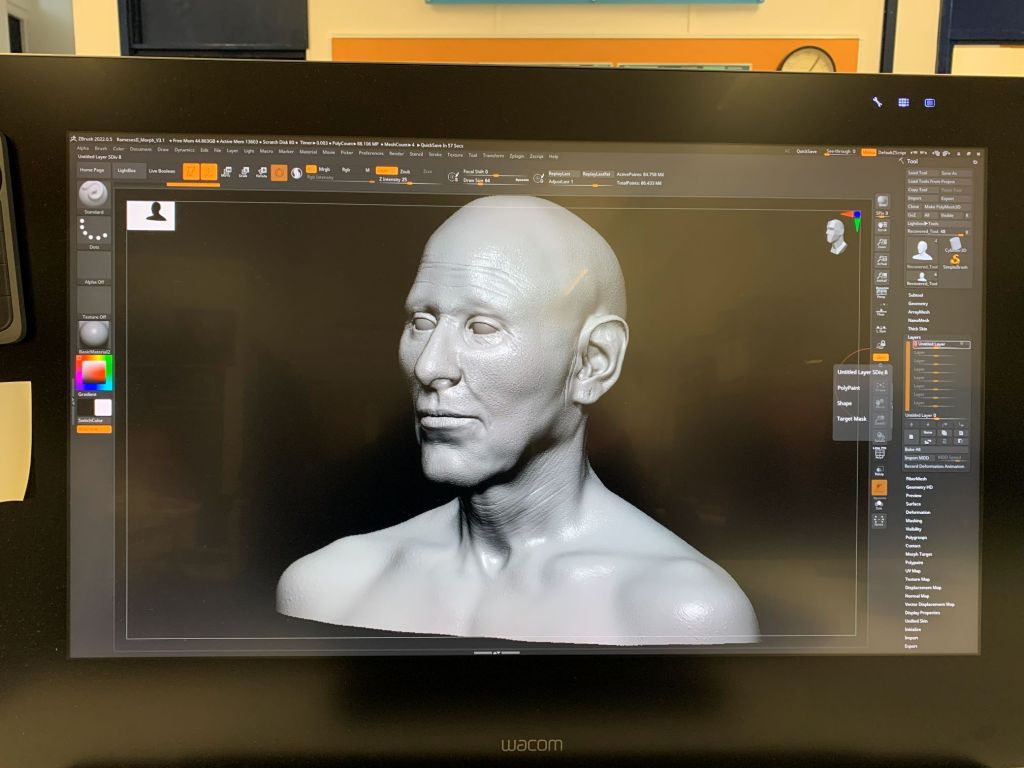

A recent project involved de-aging the face of Ramesses II – ‘a collaboration with the University of Cairo to depict the face of the Ancient Egyptian pharaoh.’ [1] Aging photographs is a process that has been used in forensics to find children who have been missing for many years but this is the first time that an aging had been done in full 3D. Ramesses died when between 87 and 92 years old. His face at death was first reconstructed from a newly made CT scan of his mummified remains, photographs and historical information. Then it was de-aged to about 45 years old – when this most celebrated of Pharaohs was at the height of his reign.

WHAT IS A ‘LIKENESS’?

Face Lab write that the result of this work is ‘not a photograph of an individual, but instead, a likeness… Therefore, a level of un-realism is sometimes preferred to establish the facial reconstruction as a depiction.’ Ramesses is deliberately left a little artificial or ‘uncanny’ looking to remind the viewer that this image is not a ‘true’ one – artifice as an ethical strategy. His facial expression is left neutral and without movement. Furthermore, the “animation of facial features to create expressions or allow the reconstruction to ‘speak’ could be viewed as disrespectful to the deceased.”

WHAT IS A LIKENESS FOR?

But what was the purpose of de-aging a king who lived over 3 thousand years ago? Do we learn anything from this apart from possibly satisfying a curiosity? These kinds of reconstruction are in fact highly valued by museums, the educational sector and the media for their ability to ‘give the public a chance to connect with history on a more personal level… making historical figures more relatable, credible, and emotionally impactful to the general public.’ The ability to see an otherwise remote figure as a distinct individual is a powerful reminder that history did happen and was shaped and experienced by real people like ourselves.

WHAT IS A FACE FOR?

Face Lab have worked on many projects that make clear how deep is our need to see others face-to-face. The Sutherland Reburial Project (2019) was initiated when human remains were discovered that had been unethically acquired by the University of Cape Town in the 1920s [3]. They had been removed from the graves where they had been originally buried and donated to the Anatomy Department without the knowledge or permission of their families.

A process of restitution was initiated for these 9 San or Khoekhoe individuals, accompanied by a range of historical, archaeological and analytical studies to document, as far as possible, their lives and deaths. Their direct descendants were traced and contacted in an effort to restore their connection with their heritage. Before returning them home for reburial, Face Lab were able to portray the faces of 8 of these individuals from their skeletal remains. The descendants had made a specific request to “see the faces of their ancestors” as part of the healing and reconciliation process. On seeing the results they “expressed amazement at the realism” and were “excitedly pointing out which bore a resemblance to living relatives.” Since this, a national policy has been established in South Africa for restitution and repatriation, influenced by the Sutherland process.

REFERENCES

1. M Roughley et al. 2024. Using a morph-based animation to visualise the face of Pharaoh Ramesses II ageing from middle to old age. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage, 35.

https://doi.org/10.1016/j.daach.2024.e00377

2. C Wilkinson. 2015. A review of forensic art. Research and Reports in Forensic Medical Science, 2015:5, 17–24.

https://doi.org/10.2147/RRFMS.S60767

3. V Gibbon et al. 2023. Confronting historical legacies of biological anthropology in South Africa—Restitution, redress and community-centered science: The Sutherland Nine. PLoS ONE 18(5): e0284785. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0284785